Robert Burns as an Exciseman

His various, ill-fated ventures as a farmer had left Burns totally disillusioned with working on the land so, just before his 29th birthday, he decided to put his education to better use by seeking a steady, well-paid job as an exciseman, (or gauger). An exciseman was employed by the government in what today would be HM Customs and Excise to ensure that people paid their taxes, particularly where related to alcohol. It was not a "trade" that was admired by the common people and it would be fare to say that excisemen at this time were, to say the least, unpopular and that attitudes towards them were, shall we say, ambivalent.

During the previous few years his new found fame as the "ploughman poet" had won him many new influential friends and acquaintances. Like many of us to this day, Burns was well aware that it was not so much about "what you know" as "who you know", when it came to job seeking. His main problem, however, was that while he was a genius as a poet and a very highly educated young man he had no work experience outside of farming. (Apart from seven months working in Irvine as a Flax Dresser.)

He decided to seek some of his new friends' patronage by letting them know that he was seeking a career change. The following letter was sent to the Earl of Glencairn, a man whom Burns genuinely admired and after whom he later named his son.

To THE EARL OF GLENCAIRN.

Edinburgh, (January 1788.)

My Lord,

I know your lordship will disapprove of my ideas in a request I am going to make to you; but I have weighed, long and seriously weighed, my situation, my hopes, and turn of mind, and am fully fixed to my scheme, if I can possibly effectuate it.

I know your lordship will disapprove of my ideas in a request I am going to make to you; but I have weighed, long and seriously weighed, my situation, my hopes, and turn of mind, and am fully fixed to my scheme, if I can possibly effectuate it.

I wish to get into the Excise: I am told that your lordship's interest will easily procure me the grant from the commissioners; and your lordship's patronage and goodness, which have already rescued me from obscurity, wretchedness, and exile, embolden me to ask that interest.

You have likewise put it in my power to save the little tie of home that sheltered an aged mother, two brothers, and three sisters from destruction. There, my lord, you have bound me over to the highest gratitude.

My brother's farm is but a wretched lease, but I think he will probably weather out the remaining seven years of it; and after the assistance which I have given, and will give him, to keep the family together, I think, by my guess, I shall have rather better than two hundred pounds, and instead of seeking, what is almost impossible at present to find, a farm that I can certainly live by, with so small a stock, I shall lodge this sum in a banking-house, a sacred deposit, excepting only the calls of uncommon distress or necessitous old age.

These, my lord, are my views: I have resolved from the maturest deliberation; and now I am fixed, I shall leave no stone unturned to carry my resolve into execution. Your lordship's patronage is the strength of my hopes; nor have I yet applied to anybody else. Indeed my heart sinks within me at the idea of applying to any other of the great who have honoured me with their countenance.

I am ill-qualified to dog the heels of greatness with the impertinence of solicitation, and tremble nearly as much at the thought of the cold promise as the cold denial; but to your lordship I have not only the honour, the comfort, but the pleasure of being your lordship's much obliged and deeply indebted humble servant,

R. B.

While Burns was much admired he was not averse to playing the nepotism card. Indeed the Webster Dictionary's definition of the word "Nepotism" could have been written around this situation, i.e., "bestowal of patronage in consideration of relationship, rather than of merit or of legal claim".

Burns's heart may have sank at the idea of "applying to any other of the great" but it did not prevent him from contacting another influential friend a week or two later. This was Mr. Robert Graham of Fintry. He had met Graham when they were both guests of the Duke and Duchess of Atholl (while visiting Blair Atholl during his tour of Scotland at the beginning of September 1787). Graham was the Commissioner of Excise for Scotland and we can speculate that it was during their meeting that Burns first thought of a career in the Excise.

To MR. ROBERT GRAHAM, OF FINTRAY.

SIR,

When I had the honour of being introduced to you at Athole House, I did not think so soon of asking a favour of you. When Lear, in Shakespeare, asked Old Kent why he wished to be in his service, he answers, "Because you have that in your face which I would fain call master." For some such reason, Sir, do I now solicit your patronage. You know, I dare say, of an application I lately made to your Board to be admitted an officer of the Excise.

I have, according to form, been examined by a supervisor, and today I gave in his certificate, with a request for an order for instructions. In this affair, if I succeed, I am afraid I shall but too much need a patronising friend. Propriety of conduct as a man, and fidelity and attention as an officer, I dare engage for; but with anything like business, except manual labour, I am totally unacquainted. [my emphasis]

I had intended to have closed my late appearance on the stage of life in the character of a country farmer; but, after discharging some filial and fraternal claims, I find I could only fight for existence in that miserable manner, which I have lived to see throw a venerable parent into the jaws of a jail, whence death, the poor man's last and often best friend, rescued him.

I know, Sir, that to need your goodness, is to have a claim on it; may I, therefore, beg your patronage to forward me in this affair, till I be appointed to a division, where, by the help of rigid economy, I will try to support that independence so dear to my soul, but which has been too often so distant from my situation.

R. B.

Burns's requests for some influence to be exerted must have worked because he was put on the roll and when the call came in the late summer of 1788 he started work as an Exciseman. At first he must have been doing OK because in September 1789, he was appointed Excise Officer for Dumfries. Later, in February 1792 he was promoted to the Dumfries Port Division, an appointment that carried a salary of £50 per annum. This was a high salary, almost twice the average at that time and coupled with his income from his poetry it placed him well into the "comfortable" bracket for the first time in his life.

Initially Burns appears to have thrown himself at the exciseman's role with enthusiasm. There are a few anecdotal and apocryphal tales of the adventures in which he became involved in his daily work. One story, which appears to be both true and documented concerns the seizing of the smuggling ship "The Rosamond" in March 1792. The ship had ran aground and despite resistance from the crew and the local population she was eventually captured. Some stories say that Burns waded into the water, sword in hand, and captured the ship single handed. This is probably just romantic nonsense but what is certainly true is that Burns was present and amongst those who took possession of the ship.

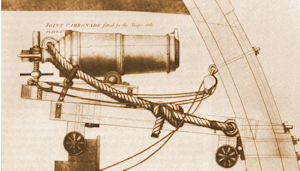

The ship and what was left of her cargo were later auctioned at Dumfries. One story has it that Burns purchased 4 carronades (small cannon manufactured by the Carron Iron Works in Stirlingshire, near Falkirk) and sent them to France to aid the revolution.The story goes that they never made it there because they were impounded by customs at Dover.There is, however, no evidence to lend credence to this story. It has also been said that this incident set Burns at odds with his government supervisors who frowned upon it as involving inappropriate behaviour for an officer of the Excise.

The ship and what was left of her cargo were later auctioned at Dumfries. One story has it that Burns purchased 4 carronades (small cannon manufactured by the Carron Iron Works in Stirlingshire, near Falkirk) and sent them to France to aid the revolution.The story goes that they never made it there because they were impounded by customs at Dover.There is, however, no evidence to lend credence to this story. It has also been said that this incident set Burns at odds with his government supervisors who frowned upon it as involving inappropriate behaviour for an officer of the Excise.

What is probably true is that Burns was already at odds with his superiors and certainly, there was to be no more promotion. There is some evidence to suggest that he was not 100% comfortable in his profession. This is illustrated in this poem, The Deil's Awa wi' th' Exciseman (The Devil has Taken the Exciseman).

The deil cam fiddlin' thro' the town,

And danc'd awa wi' th' Exciseman,

And ilka wife cries, "Auld Mahoun,

I wish you luck o' the prize, man."Chorus-The deil's awa, the deil's awa,

The deil's awa wi' the Exciseman,

He's danc'd awa, he's danc'd awa,

He's danc'd awa wi' the Exciseman.

We'll mak our maut, and we'll brew our drink,

We'll laugh, sing, and rejoice, man,

And mony braw thanks to the meikle black deil,

That danc'd awa wi' th' Exciseman.

The deil's awa, &c.

There's threesome reels, there's foursome reels,

There's hornpipes and strathspeys, man,

But the ae best dance ere came to the land

Was-the deil's awa wi' the Exciseman.

The deil's awa, &c.

Further evidence for Burns's lack of esteem for his position as an exciseman is provided in this letter that he sent to Mr. Hill, the Edinburgh Bookseller a few months after his original appointment. (Note also that like many of us today, he saw the use of company stationery for personal purposes as being quite acceptable.)

To MR. HILL, BOOKSELLER, EDINBURGH. ELLISLAND, 2nd April 1789

I will make no excuse, my dear Bibliopolus(God forgive me for murdering language!) that I have sat down to write you on this vile paper.

It is economy, Sir; it is that cardinal virtue, prudence; so I beg you will sit down, and either compose or borrow a panegyric. If you are going to borrow apply to ... to compose, or rather to compound, something very clever on my remarkable frugality; that I write to one of my most esteemed friends on this wretched paper, which was originally intended for the venal fist of some drunken exciseman, to take dirty notes in a miserable vault of an ale-cellar.

R. B.

Burns lived out what was left of his short life in the employment of the Excise in Dumfries. From late 1795 until his death on 21st July 1796 he was in extremely poor health as his last few poignant letters confirm. Towards the end he had rather strangely been advised by his doctor and friend (Dr. Maxwell) that bathing in the sea on the Solway Firth would alleviate his problems.

Burns lived out what was left of his short life in the employment of the Excise in Dumfries. From late 1795 until his death on 21st July 1796 he was in extremely poor health as his last few poignant letters confirm. Towards the end he had rather strangely been advised by his doctor and friend (Dr. Maxwell) that bathing in the sea on the Solway Firth would alleviate his problems.

All this did was hasten him to his grave but he appeared to be feeling the pinch again, his salary having been reduced to £35 on account of his sickness. On 7th July, he appealed to his old friend, the lawyer Alexander Cunningham, for help from his "Brow, Sea-bathing Quarters."

(The Brow Well - pictured above - is a little tank that was used as a mineral spring in the Parish of Ruthwell, about 10 miles from Dumfries. Burns had been advised to go there by Dr. Maxwell to drink the foul tasting spring water in the hope that it would alleviate his symptoms.)

TO MR. CUNNINGHAM.

BROW, Sea-bathing quarters, 7th July 1796.

My Dear Cunningham,

I received yours here this moment, and am indeed highly flattered with the approbation of the literary circle you mention; a literary circle inferior to none in the two kingdoms. Alas! my friend, I fear the voice of the bard will soon be heard among you no more!

For these eight or ten months I have been ailing, sometimes bedfast and sometimes not; but these last three months I have been tortured with an excruciating rheumatism, which has reduced me to nearly the last stage. You actually would not know me if you saw me. Pale, emaciated, and so feeble, as occasionally to need help from my chair-my spirits fled! fled!-but I can no more on the subject-only the medical folks tell me that my last and only chance is bathing and country quarters, and riding.

The deuce of the matter is this-when an exciseman is off duty, his salary is reduced to £35 instead of £50. What way, in the name of thrift, shall I maintain myself, and keep a horse in country quarters, with a wife and five children at home, on 35 pounds? I mention this, because I had intended to beg your utmost interest, and that of all the friends you can muster, to move our Commissioners of Excise to grant me the full salary; I dare say you know them all personally. If they do not grant it me, I must lay my account with an exit truly en poete; if I die not of disease, I must perish with hunger.

I have sent you one of the songs; the other my memory does not serve me with, and I have no copy here, but I shall be at home soon, when I will send it you. Apropos to being at home, Mrs. Burns threatens in a week or two to add one more to my paternal charge, which, if of the right gender, I intend shall be introduced to the world by the respectable designation of Alexander Cunningham Burns. My last was James Glencairn, so you can have no objection to the company of nobility.

Farewell

R. B.

(This request was not granted.)

Burns's health continued to deteriorate and his last letter was to his to his father in Law, James Armour, requesting that he send his wife to help with the birth of their latest child which was due at any time.

To HIS FATHER-IN-LAW, JAMES ARMOUR, MASON, MAUCHLINE.

DUMFRIES, 18th July 1796.

MY DEAR SIR,-Do, for heaven's sake, send Mrs. Armour here immediately. My wife is hourly expecting to be put to bed. Good God! what a situation for her to be in, poor girl, without a friend!

I returned from sea-bathing quarters to-day, and my medical friends would almost persuade me that I am better, but I think and feel that my strength is so gone that the disorder will prove fatal to me.

Your son-in-law,

R. B.

Sadly Robert Burns died three days later. His wife gave birth to their last child, Maxwell Burns, at home while the funeral ceremony was being held on 26 July 1796.

Bryan Weir, December 2004.